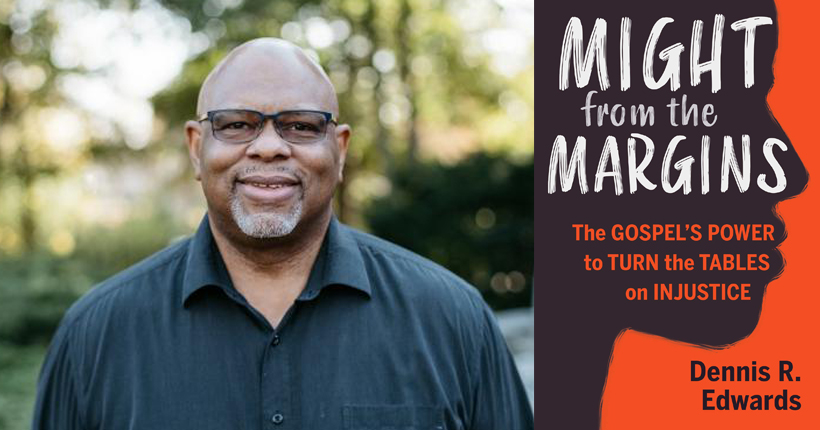

Rev. Dennis Edwards, PhD is such an important theologian, not just to me personally, but for the times in which we’re living. In Might From the Margins, his most recent book, he shows once again why his voice, his experience, his expertise are so vital. In fact, much of the book is making the argument that voices like his are particularly helpful, insightful, and important to heed. Why is that? Because that is how God has chosen to be revealed.

I vividly recall when a friend (shout out to Morgan Guyton) pointed out to me that First Corinthians chapter one verses 27 and 28 aren’t talking about “things” like so many English translations would have you and me believe. No, Paul is talking about People!

“Brothers and sisters, think of what you were when you were called. Not many of you were wise by human standards; not many were influential; not many were of noble birth. But God chose the foolish ONES of the world to shame the wise; God chose the weak ONES of the world to shame the strong. God chose the lowly ONES of this world and the despised ONES—and the ONES that are not—to nullify the ONES that are, so that no one may boast before him.” (my translation)How odd and unsurprising that modern English translators have overlooked this. But Dennis Edwards has not. He draws our attention to the marginalized ones, the Diaspora, the ones to whom modern Westerners (particularly White Evangelicals) don’t often look for theological or spiritual expertise. He reminds us that these sisters and brothers are the ones God has chosen.

“…marginalized people are often more spiritually keen than those within mainstream culture. God has given spiritual insight to many people who were deprived of society’s advantages. God honors people of low status and operates through people and circumstances that appear foolish in the eyes of those lacking spiritual awareness.” (p.162)This is a vitally important message for Western Christians today. Might From the Margins draws our attention to the way power factors into our understanding of the Christian faith. Power is something that White Evangelicals in particular have a difficult time talking about. It’s something that makes them/us uncomfortable. Which is precisely why White Evangelicals need to read this book. In fact, to me, chapter five alone is worth the cost of this book all by itself.

The Power of Anger

There are so many good chapters in this power-packed little book, but chapter five stuck out to me. In it, Dr. Edwards flips the script on anger, showing that not only is anger Not a sin, it is the appropriate response to injustice. Jesus got angry at injustice! Paul did too. Dr. Edwards points this out with great ease and skill. “When we are confronted with evil, anger is among a range of appropriate reactions.” (p.92) In fact, I wrote in the margins of my copy a question that all too often goes unasked: “Who gets to be angry and who doesn’t?” The power of anger may not be often thought of as a positive trait, but is almost universally respected, even feared. White Evangelicals (and White Americans more generally) fear the anger of racial minorities. They/we fear retribution for the injustices they/we have perpetrated upon others or have unconsciously participated in. But they/we happily embrace the power of anger when it benefits us. White male rage isn’t merely tolerated in the dominant culture of America, it’s often celebrated. But, as Dr. Edwards points out, White anger isn’t just momentary explosions of emotion. White anger is sown into the fabric of American society.“White anger impacts politics and systems. For example, lynching was the result of white anger after the Civil War—systematic terror was inflicted on people of color. White anger restricted voting rights for people of color. White anger opposed school desegregation. White anger placed obstacles to home ownership for black people and other people of color. White anger undergirded the violence against peaceful protestors during the civil rights era.” (p.95)

Who gets to be angry in a society designed to support the empowerment of White people and the disempowerment of people of color?

But Jesus shows us what to be angry about. Jesus is angered when religious leaders cling to an interpretation of the Scriptures that overlooks the suffering or perpetuates their pain. Dr. Edwards draws our attention to Jesus’s anger in Mark chapter three. In this story Jesus heals a man with a withered hand on the Sabbath.“The onlookers in the story included Jewish religious leaders... Those onlookers were more concerned about Jesus violating Sabbath laws than they were about the man with the withered hand. It is common today for religious people to appeal to law and order rather than focus on real people and their needs. [...] Jesus, however, centers the man with the withered hand. Jesus questions the onlookers about the right course of action: doing good versus doing harm, saving life versus killing. The choice should be obvious, so Jesus performs the miracle to make clear that human wholeness is more important than laws—even ones held to be sacred. [...] The hard-hearted people were more interested in Jesus upholding their traditions than in the man's predicament. [...] Perhaps it is still the case that Jesus is angry with those who are concerned more with prohibitions than with human flourishing.” (p.97-98)Unlike the anger of Jesus, White anger seeks to preserve the unjust power differentials that prop up the lie of White Supremacy. Jesus’s anger, by contrast, sides with those who are on the receiving end of injustice. Jesus’s anger is empowered by his compassion for those who are suffering. But Dr. Edwards doesn’t stop there. Not only is Jesus’s anger good; so is Paul’s. In Acts 16, Paul is beaten and jailed unjustly. He is a Roman citizen and that entails certain rights.

“[Acts 16 is] a story about Paul becoming indignant when his personal rights were violated. That story is especially significant for marginalized people because Christians in the dominant culture oftentimes either minimized any notion of civil rights for minorities and women or denounced protests designed by the oppressed to assert their civil rights.” (p.100)In Acts 16, Paul is vigilant to remind the Roman authorities who unjustly treated him that they are accountable before the law. Paul protests his mistreatment, demands justice, and holds their feet to the fire using the same standard by which he is held. These are things I’ve heard dozens and dozens of White Evangelicals tell me is incompatible with “the Gospel.” I guess the Apostle Paul didn’t get that memo. In fact, it’s of particular significance that Dr. Edwards, who has himself been influenced by Anabaptist theology—and is writing this book for an Anabaptist publisher—is pointing out this biblical paradigm for protest and civil rights. In my experience, White (Neo)Anabaptists and other White Evangelicals influenced by Anabaptist thought have wrongly concluded that protest, political activism, and calls for social justice run counter to the values of Anabaptism—values like being counter-cultural, being peace-makers, and being nonviolent. But Dr. Edwards is not alone. He stands with other Neo-Anabaptist thinkers and theologians like Shane Claiborne and Drew Hart (among others). I’m really grateful that he has lent his scholarly and pastoral weight to this matter.