Some Christians think God became a Savior only after the historical crucifixion of Messiah Jesus of Nazareth. For these Christians, God is not a Savior essentially, but incidentally. "Saving" is an activity God could do without; it's not something God "has to do." God is a Savior as a result of historical events, not because it is who God is in God's very nature. If humanity has not sinned, Jesus Christ would not have been 'necessary,' and God would not be a Savior.

Depending on your theological perspective, this belief could either appear common sensical or absurd. If you're coming from a Western, conservative, evangelical (Protestant) perspective, you likely find the belief that God became a Savior obvious. And it might be equally obvious that this is why Christians should worship God—because God has saved Christians by the Cross and Resurrection of Jesus. This makes sense to Western Christians because of Western culture. It is the individualism of Western culture that distorts salvation history into God's "plan of salvation" for humanity. And it is the consumerism of Western culture that makes God's praise about the salvation humanity has received."God does what God does because of us, and we worship God because of what we get from God."

Western Christians will argue that they hold this view for two important reasons. First, they claim that this view preserves and secures God's "freedom." They argue that were God a Savior in God's very nature, God would not be "free" to not save humanity. They claim this would introduce "necessity" into the nature of God. Second, they claim that it safeguards salvation as a gracious gift from God. Were salvation not something which God could have withheld from humanity, salvation would no longer be "grace" (a gift) freely given. Thus, they speculate that God could exist without communicating salvation.

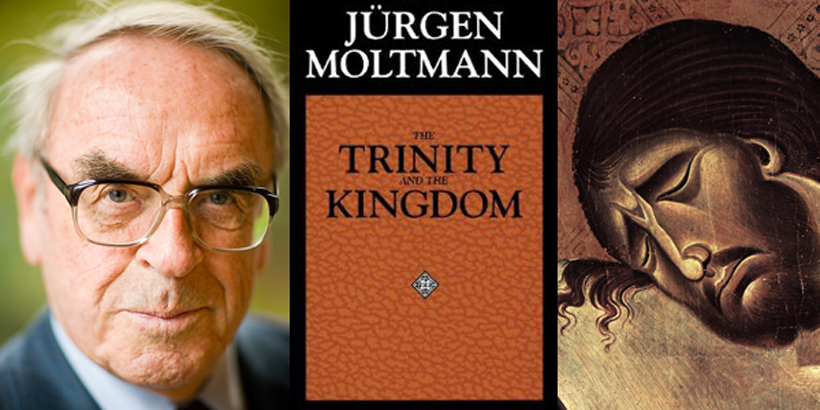

However, in chapter 5 of The Trinity and the Kingdom, Jürgen Moltmann directly confronts this conception of God in a section called "The Doxological Trinity."1 He makes several arguments, which dismantle this view, rooted in Scripture, the tradition of the Church, and the doctrine of the Trinity.

I. God Does What God Is

"God is love." - 1 John 4.16

Moltmann begins his critique with background on the historical, theological disjunction of the Godhead by the use of the speculative labels "immanent Trinity" and "economic Trinity" to distinguish between the saving activity of God in the world as opposed to who God is in Godself.Ever since the repulse of modalism through Tertullian, it has been usual to distinguish between the economic and the immanent Trinity. The economic Trinity designates the triune God in his dispensation of salvation, in which he is revealed. The economic trinity is therefore also called the revelatory Trinity. The immanent Trinity is the name given to the triune God as he is in himself. The immanent Trinity is also called the substantial Trinity. (p.151)This distinction in God effectively creates two "trinities": one Trintiy who is self-sufficient, Pollyannish, indifferent to the world, and one Trinity who incarnates love in the Person of Jesus Christ. Why these two "trinities" have not met one another, who can know? But the distinction is justified by the assumption that we can only know what God is like in God's "economic Trinity" while only learned theologians can tell us what God is like in God's "immanent Trinity". This theological division in the Godhead mirrors the political division between the scholastic clergy and the pious laity. Only the clerics can know the "secret" nature of God, while laypersons are given the breadcrumbs from the theologians' table. But Moltmann will have none of that!

This distinction cannot mean that there are two different Trinities. It is rather a matter of the same triune God as he is in his saving revelation and as he is in himself. Is this distinction between God for us and God in himself a speculative one? And if it is speculative, is it necessary? (p. 151)Great question Jürgen! I have a feeling you're going to tell us!

This distinction between immanent and economic Trinity would be necessary if, in the concept of God, there were really only the alternative between liberty and necessity. But if God is love, then his liberty cannot consist of loving or of not loving. On the contrary, his love is his liberty and his liberty is his love. He is not compelled to love by any outward or inward necessity. Love is self-evident for God. So we have to say that the triune God loves the world with the very same love that he himself is. (p. 151)Some Christians conceptualize God as completely self-sufficient in Godself, to the point that creation is less than an afterthought. This is the classic "Pollyanna" god. The god who does not care about the suffering of the world, about injustice, or about evil. This god is content in his own self-love and bliss. But does this conception of God correspond to the God revealed in Jesus Christ—the Jesus Christ who came into the world to destroy the works of the Devil, the Jesus Christ who healed and delivered humans from disease and demonization? Of course not! Everyone and anyone who has read the Gospels can clearly see that the Evangelists intend to teach that Jesus's birth, ministry, teachings, life, death, resurrection, and ascension reveal a God with the same character and nature. The conception of a self-loving, blissful, Pollyanna god in the sky is not the God revealed in Jesus Christ.

The notion of an immanent Trinity which God is simply by himself, without the love which communicates salvation, brings an arbitrary element into the concept of God which means a break-up the Christian concept. Consequently this idea safeguards God's liberty nor the grace of salvation. It introduces a contradiction into the relationship between the immanent and the economic Trinity: the God who loves the world does not correspond to the God who suffices for himself. Before the unchangeable God, everything is equal and equally indifferent. For the loving God, nothing is a matter of indifference. Before an equivocal, an undecided God, nothing is significant. For the God who in his love is free, everything is infinitely important. But the immanent and the economic Trinity cannot be distinguished in such a way that the first nullifies what the second says. The two rather form a continuity and merge into one another. (p. 151-152)Moltmann exposes the inadequacy of the theological disjunction of the Godhead. It does not accomplish what its proponents believe it does. It does not safeguard grace or God's freedom. Instead, it enslaves God in a prison of lovelessness. It shackles God inside indifference and apathy. God can only love Godself. God doesn't have enough love for the world. In place of the diminished God of this "immanent" and indifferent Trinity, Moltmann places the united Trinity whose love is infinite and more than enough for the world. In the love of the united Trinity, everything is significant and infinitely loved. What a more glorious and praiseworthy vision of God!

II. God Saves Us By Giving Us Godself

"His divine power has given us everything we need for a godly life through our knowledge of him who called us by his own glory and goodness. Through these he has given us his very great and precious promises, so that through them you may participate in the divine nature, having escaped the corruption in the world caused by evil desires." - 2 Pet. 1.3-4

This united Trinity upon which Moltmann expounds is revealed in Salvation History as the Loving Savior, the Savingly Loved One, and Saving Love Itself. The united Trinity is also the God worshipped in the Church of Jesus Christ. Here, Moltmann turns to church history and historical theology. He addresses the theological disjunction of the Godhead from the standpoint of worship.The other and specific starting point for distinguishing between the economic and the immanent Trinity is to be found in doxology. The assertions of the immanent Trinity about eternal life and the eternal relations of the triune God in himself have their Sitz im Leben, their situation in life, in the praise and worship of the church: Glory be to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Ghost! Real theology, which means the knowledge of God, finds expression in thanks, praise and adoration. And it is what finds expression in doxology that is the real theology. There is no experience in doxology that is the real theology. There is no experience of salvation without the expression of that experience in thanks, praise and joy. An experience which does not find expression in this way is not a liberating experience. Only doxology releases the experience of salvation for a full experience of that salvation. In grateful, wondering and adoring perception, the triune God is not made man's object; he is not appropriated and taken possession of. It is rather that the perceiving person participates in what he perceives, being transformed into the thing perceived through his wondering perception. Here we know only in so far as we love. Here we know in order to participate. Then to know God means to participate in the fullness of the divine life. That is why in the early church the doxological knowledge of God is called theologia in the real sense, being distinguished from the doctrine of salvation, the oeconomia Dei. The 'economic Trinity' is the object of kerygmatic and practical theology; the 'immanent Trinity' the content of doxological theology. (p. 152)Since the united Trinity is love, and love is essence of the saving activity of God in the world, it is clear that God's salvation is God's giving of Godself to humanity—the participation of humanity in God's very nature of love. There is no greater gift God can give humanity than Godself. God is not a means to some other end. No, God in God's Cruciform Love is the telos of Christian faith!

In doxology the thanks of the receiver return from the goodly gift of the giver. But the giver is not thanked merely for the sake of of his good gift; he is also extolled because he himself is good. So God is not loved, worshipped and perceived merely because of the salvation that has been experienced, but for his own sake. That is to say, praise goes beyond thanksgiving. God is recognized, not only for his goodly works but in his goodness itself. And adoration, finally, goes beyond both thanksgiving and praise. It is totally absorbed into its counterpart, in the way that we are totally absorbed by astonishment and boundless wonder. God is ultimately worshipped and loved for himself, not merely for salvation's sake. (p. 153)When we worship God, we give praise and glory and honor to God not merely for the saving activity of God, but even more profoundly for who God is in Godself. God is the love in whom we live, move, and have our being as persons and as God's children (Acts 17.28)! God is the ocean in which we swim! The Crucified Christ is the One by whom, for whom, and to whom all things have existence (Col. 1.15-20)! There is no greater experience of salvation than the exuberant, ecstatic shalom that overflows from being caught up in the triune love who is God.

III. God is Faithful to Godself

"[God] cannot deny himself." - 2 Tim. 2.13

Since God does what God is and God saves humanity by giving us Godself, God's being is consistent with God's saving activity. There is tautology in the Christian concept of salvation. God is love and God saves by giving humanity the saving love that God is. This correspondence between who God is and what God does reinforces our trust in God. God is Truth and God is true to Godself in the communication of God's self. This is why we can trust that God's promises are true and God's Word is Truth.It follows from this interlacing of the doctrine of salvation with doxology that we may not assume anything as existing in God himself which contradicts the history of salvation; and, conversely, may not assume anything in the experience of salvation which does not have its foundation in God. The principle that the doctrine of salvation and doxology do not contradict one another is founded on the fact that there are not two different Trinities. There is only one, single, divine Trinity and one, single divine history of salvation. The triune God can only appear in history as he is in himself, and in no other way. He is in himself as he appears in salvation history, for it is he himself who is manifested, and he is just what he is manifested as being. Is this a law which infringes God's liberty? No, it is the quintessence of God's truth. God can do anything, but 'he cannot deny himself' (II Tim. 2.13): 'God is faithful.' Consequently we cannot find any trinitarian relationships in salvation history which do not have their foundation in the nature of the triune God, corresponding to him himself. It is impossible to say, for example, that in history the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father 'and from the Son', but that within the Trinity he proceeds 'from the Father alone'. God's truth is his faithfulness. Consequently we can rely on his promises and on himself. A God who contradicted himself would be an unreliable God. He would have to be called a demon, not God. The true God is the God of truth, whose nature is eternal faithfulness and reliability. That is why the principle behind the Christian doctrine of the Trinity is:

Statements about the immanent Trinity must not contradict statements about the economic Trinity. Statements about the economic Trinity must correspond to doxological statements about the immanent Trinity. (p. 153-154)Therefore, in conclusion, there is no "Polyannish", "unchangeable", indifferent, god in the sky—that conception of God is either an idol or a demon. The only God who exists for the Christian is the God revealed in Jesus Christ—the God who is Cruciform Love. God is Loving Savior because of who God is (self-sacrificing Love), not because of who humanity is (sinful). The Cross doesn't make God a Savior; the Cross reveals that God Already Is (and Always Has Been) a Savior.

Glory and Honor and Praise, all Power and Majesty be to the God who is Cruciform Love—the God whose eternal nature is made known in King Jesus! Amen.

1. Jürgen Moltmann, The Trinity and the Kingdom (Fortress Press, 1981), 151-154.