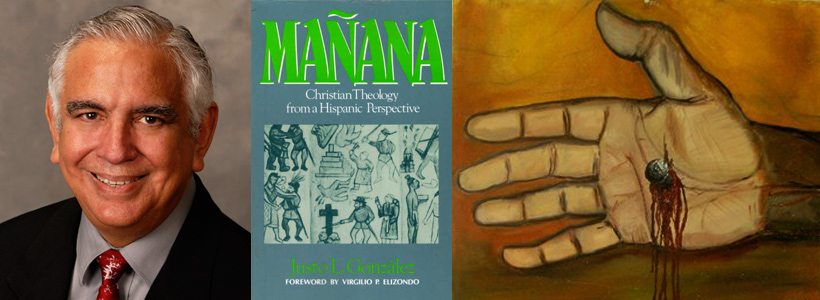

We’ve finally arrived at the fifth and final installment of this series on the ‘politics of impassibility,’ looking deeply into an important book: Mañana 1 by world-renowned, Hispanic theologian and historian Justo González. Be sure to check out the rest of the series (one, two, three, four).

In part four, we drew readers’ attention to the ninth and tenth chapters of Mañana: “On Being Human,” “And the Word Was Made Flesh” respectively. Part four focused on chapter nine and so we’ll now turn our focus to chapter ten.

1. Justo González, Mañana: Christian Theology from a Hispanic Perspective (Abingdon, 1990) [http://a.co/d/41ETGLR]

The Constantinization of the Church Meets the Stubbornness of Jesus

González begins chapter ten with a look back at Nicea. As he did in previous chapters, he commends the bishops for their resistance to the Arian attempt to import the Greek concept of deity (i.e. immutability, impassibility, etc.) into Christian theology by unequivocally affirming the fully eternality and divinity of Jesus Christ. They proclaimed Jesus “very God” and “of the same substance with the Father” to silence any notion that God is ‘above’ the feelings and movement (i.e. passibility) of human life. Messiah Jesus of Nazareth, who was fully human and fully divine suffered, therefore it is true to say God suffered. Nevertheless, González laments that the council did not go far enough in preventing the “Hellenization—and therefore the Constantinization—of God.” (p.139) By this González means that by utilizing the Greek concept of “essence” (ousia) to describe the divine nature, the bishops inadvertently imported a “basically static” conception of God into the history of the revelation of the dynamic, Living God of the Bible. This, he marks as an important misstep. He traces this error back to the beginnings of Christianity’s adoption of Greek philosophy and metaphysics:“Although the Council of Nicea, in affirming the eternal divinity of the Word, avoided the extreme ‘Constantinization’ of God, it did not go so far as to state that immutability is not a characteristic properly to be applied to the Christian God. On the contrary, in speaking of the ‘essence’ (ousia) of God, it did imply that God could most properly be spoken of in terms of the Greek notion of substance, which is basically static. Therefore, the process begun two centuries earlier with Justin—and even before that with Philo—and of which the Trinitarian controversies were an expression, was not stopped by the Council.” (p.139)Recall that González is keen to expose the socio-political ramifications of the Christological debates. So he immediately moves into charting the process by which Christian theology began to be de-Christianized.

“Such Constantinization was a relatively simple matter. After all, ‘No one has ever seen God.’ All that was necessary was to bring about a change in people’s minds as to who God is. In order to do this, the Greek notion of being was readily available. By showing the ‘rationality’ of this notion—on the basis that only the fixed and given is strictly rational—and the anthropomorphism of the images with which Scripture and early Christian theology described the living God, the exponents of the theology of the status quo were able to do away with a great deal of the biblical picture of an active, just, loving, and avenging God. At the same time, allegorical interpretation dehistoricized the Bible, and thus God’s activity in history was transmuted into perennial and supposedly ‘higher’ meanings. The pharaohs of the Roman Empire and of Western Civilization became the ‘new Israel,’ while secretly hoping that God would not upset the applecart of society, as had been done in Egypt of old.” (p.139, emphasis mine)A living God of the Bible, who acts in history, is filled with passion, love, and justice was despised by the Greek philosophers. A God who suffers on the Cross was “foolishness” to them, says Paul. (I Cor. 1.18—25) The only proper way of conceptualizing God was as unmoved by this creaturely world of movement, untouched by the passion that affects human beings, unsullied by the evil of matter. So, the Scriptures had to be stripped of those unsightly anthropomorphisms which depicted God as being moved by compassion, anger, love, and justice. Such notions weren’t “rational” enough! At the same time this is going on, the Scriptures are also being decoupled from their historical context in the life of the nation of Israel. Then the promises made to a beaten and battered tribe can be appropriated by one of the empires who beat and battered them! Pharaoh is transformed into Moses and Rome is transformed into Israel! There’s just one small problem with that scheme: Jesus. Messiah Jesus of Nazareth stubbornly stands in the way of Constaninization. His story—which is also the story of our redemption—clings unrelentingly to the historical context in which it took place: “...Born of the Virgin Mary, Suffered under Pontius Pilate...” Jesus’s story refuses to be transformed into an empire-building program.

“...there was one irreducible fact that refused to be Constantinized. This fact was Jesus, the carpenter from Galilee who was called the Christ. Although ‘no one has ever seen God,’ here was one whom people had not only seen but also heard and even touched (I John 1:1). Here was a historical figure whom one must take into account. Great pains were taken to mitigate the scandal of God’s being revealed in the poor carpenter. His life and sayings were reinterpreted so as to make them more palatable to the rich and powerful. Innumerable legends were built around him, usually seeking to raise him to the level that many understood to be that of the divine—that is, to the level of a superemperor. Art depicted him as either the Almighty Ruler of the universe, sitting on his throne, or as the stolid hero who overcomes the suffering of the cross with superhuman resources and aristocratic poise. Even after all this was said and done, there still remained the very real and very human figure of the carpenter crucified by the ruling powers, crying in his distress, and yet declared to be ‘very God.’ This was and is the stumbling block that no form of Constantinian theology can overcome.” (p.140, emphasis mine)

Gnostic-Docetism: Another Way to Relativize Jesus

Fear is a major impediment to freedom. The children of Israel clung to the idols of Egypt out of fear of what it would mean to follow YHWH into the desert as a free people. Yes, freedom is risky—and following the Living God entails risk—but there is no better risk to take! The Greek conception of God, the essentially static, unmoved, unfeeling god is more secure for those too anxious to follow the untamed God.“Freedom and dignity are always costly, as the Israelites discovered when they began missing the leeks, onions, and security of Egypt. To follow the living God means that one—an individual or an entire people—must abandon the security of all idols. It means taking the initial risk of believing in this God who is like no other god. And it means taking the further risk of challenging structures of injustice and oppression, trusting that the living God shares in the struggle.” (p.140, emphasis mine)If the Jesus who is rooted in history is not so easily Constantinized, then there is another way to relativize him: Gnostic-Docetism. There is a false piety to placing God outside our experience. God is “too great” to suffer as we suffer. God is “too holy” to be moved by our suffering. The world of matter is beneath the Supreme Being, such a god cannot even be thought to muck about in it. This way of thinking leads to a Christ who only *Seemed* to be human, but was really only divine all along.

“Jesus did not really come in the flesh but only appeared to do so. This view of Jesus, called docetism, had great appeal for many Christians, for it seemed to exalt Jesus by declaring him to be a purely heavenly and divine creature. Likewise, according to the docetists, our suffering and death, as well as all the injustice and evil that exists in the world, are not important. Our bodies are prisons holding our souls in this material world and clouding our vision of spiritual realities. But when all things are consummated, our bodies and indeed all matter will be destroyed, and there will be nothing but spiritual realities.” (p.141, emphasis mine)

“...docetists seemed to be giving Jesus greater praise than did the more orthodox Christians, who insisted that Jesus was a human being, who needed to eat just as we need to eat and who was capable of suffering just as we suffer.” (p.142, emphasis mine)This is often the case with Christological heresy: it errors in an attempt to preserve Jesus from his own humanity. “Surely Jesus whom we worship as God cannot be thought to suffer, since God cannot suffer,” is the thought. That’s how the false god of Greek philosophy attempts to relativize the God of the Bible and the Jesus of the Gospels. But the real Jesus isn’t so easily pushed around.

“The most important stumbling block gnosticism found in its way was the person of Jesus Christ. The Gospels and Christian tradition made it quite clear that he was no ethereal phantom flouting in the clouds and speaking mysterious words. On the contrary, the Gospels spoke of him as being born at a particular time and place. They spoke of him as growing, eating, sleeping, weeping, perspiring, bleeding, and even dying. The Fourth Gospel affirmed that ‘the Word was made flesh.’ Indeed, the Christian message could be spoken of as that ‘which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon and touched with our hands.’ (I John 1:1). The notion that the supreme revelation of God had taken place in such a person made it clear that spiritualist escapism was not the Christian way. [...] Docetism, while seeming to glorify Jesus, in truth deprived him of what in the New Testament is his greatest glory: his incarnation and suffering on the cross. In the last analysis, what docetism denied was not only the reality of the incarnation and the suffering of Jesus but the very nature of a God whose greatest victory is achieved through suffering, and whose clearest revelation is in the cross.” (pp.142-143, emphasis mine)Gnostic-docetism attempts to preserve the immutable, impassible god of Greek philosophy—which projects those attributes upon the powers that be. God becomes emperor-like so that the emperor can become god-like. But is the solution to deny the eternal divinity of the Word?

Rugged Individualism and the Self-Made God

Christological heresies that deny the eternal divinity of the Word are called “adoptionism." It is “declared that Jesus was ‘mere man’ who somehow had been adopted into divine sonship.” (p.144) But rather than being the cure to Constantinization, this heresy is also used to oppress the powerless. González connects adoptionism to the myth that ‘anyone can make it.’“Those who belong to the higher classes have a vested interest in this myth, for it implies that their privilege is based on their effort and achievement. But those who belong to the lower classes and who have not been propagandized into alienation from their reality know that this is a myth, and that few that do make it are in fact allowed to move on in order to preserve the myth.” [...] Adoptionism is seen as an alienating doctrine by those who realize that their society is in fact closed. One of us making it is important; but it does not end the basic structure of injustice, which is the real issue.The one who ‘makes it’ must be more than simply another one of us, more than the proof that oppression is not all that real after all. The one who ‘makes it’ must also be the expression of a reality beyond our closed reality. Jesus Christ must be more than the first among the redeemed, more than the local boy who makes good. He must also be the Redeemer, the power from outside who breaks into our closed reality and breaks its structures of oppression. He must be more than the ‘adopted son of God.’ He must be God adopting us as sons and daughters.” (pp.144-145, emphasis mine)It’s clear that adoptionism can be just as oppressive as docetism, but for different reasons. Both heresies fail to declare Jesus’s full divinity and full humanity simultaneously. Hence, Chalcedon.

The Chalcedonian Parameters

At Chalcedon, the church declared that “in Jesus Christ, and for us and our salvation, the divine and the human have been joined.” (p.145) But because of the infiltration of pagan, Gentile philosophy, “human” and “divine” held contradictory connotations:“In effect, what the church had done in accepting the notion of God as impassible, immutable, infinite, omnipotent, and so forth, was to define God in terms of negation of all human limitations. We are finite; God is infinite. We are subject to change; God is impassible. Our power is limited; God is omnipotent. God is whatever humans are not, and vice versa. These mutually exclusive understandings of both divinity and humanity were known and defined a priori, quite apart from the incarnation.” [...] “The inescapable paradox of the incarnation, that this particular man is also the universal God, is turned into a contradiction when the terms of the union are stated on the basis of a supposed a priori knowledge of what it means to be human and what it means to be divine.” (pp.145-146, emphasis mine)Rather than starting from where Scripture points for God’s self-revelation (i.e. Jesus, particularly on the cross), some Christians started out (and still do to this day!) with a unbiblical notion divine and human as mutually exclusive categories. If the Incarnation and Cross of Jesus are a Christian’s starting place for God’s self-revelation, then the truth is that divinity and humanity aren’t contradictory and have been joined. God does suffer! Humanity can be glorified! Chalcedon only set the parameters: Jesus is at once fully God, fully human. But at least two ‘schools’ emerged that worked out that formula slightly differently. They were the Alexandrian and the Antiochene. The Alexandrian ‘school’ had what’s been called a “unitive” Christology—meaning, they were sure to affirm both Christ’s divinity and humanity. However, their articulations often bordered on docetism. The Antiochene ‘school’ had what’s been called ‘disjunctive’ Christology. They “insisted on the full humanity of Jesus, and also on his full divinity, but feared that too close a union between the two would result in the humanity being swallowed up in the divinity.” (p.146) While these schools are emerging, Arianism has not been fully eradicated. So, in an attempt to explain the joining of divine and human natures in Christ, Apollinaris (of the Alexandrian school) came up with a compromising articulation:

“Jesus was physically human, but that psychologically he was purely divine. [...] According to [Apollinaris], the mutable body could be joined to the immutable Son, thus preserving both the union of the divinity and humanity and the immutability of the Son.” (p.147)Building on González’s previous chapter on human nature (see part four of this series), he points out the error of Apollinaris’s view:

“Apollinaris’s view of the incarnation in fact denied that God had been joined to a true human being. A human being is not just a body in which a mind resides but is both a body and a mind. What Apollinaris proposed was a partial incarnation. The consequence of such a partial incarnation would be a partial salvation.” (p.147, emphasis mine)Then González quotes Gregory Nazianzen who said, “For that which [the Son] has not assumed He has not healed.” Thankfully, Apollinarianism as rejected at the Council of Constantinople in 381. The next heresy to form because of disjunctive Christology was Nestorianism. Since Nestorius held the same mutually exclusive categorical conceptions of divinity and humanity that the pagan, Gentile philosophers taught he objected to the use of the term “theotokos” (bearer of God) for Mary, Jesus’s mother. Nestorius could not reconcile Jesus’s human and divine natures, so he sought to preserve them both by keeping them separate—so separate in fact that his view was condemned at the Council of Ephesus in 431. Instead, the church adopted the doctrine of communicatio idiomatum “...the doctrine that in the incarnation the union of divinity and humanity is such that what is predicated on one can be also be predicated on the other.” (p.148) Nestorianism is a heresy because, “the constant distinction between the two ‘natures,’ without a real union between the two, denied the reality of the incarnation.” González shows why Nestorianism is a particularly unbiblical heresy:

“Nestorianism has never been a temptation for Hispanic Christians. The reason for this is that we feel the need to assert that the broken, oppressed, and crucified Jesus is God. A disjunction between divinity and humanity in Christ that denies this would destroy the greatest appeal of Jesus for Hispanics and other groups who must live in suffering. [...] The suffering Christ is important to Hispanics because he is the sign that God suffers with us. An emaciated Christ is the sign that God is with those who hunger. A flagellated Christ is the sign that God is with those who must bear the stripes of an unjust society. [...] Nestorianism denies that God took these up. For this reason, the Nestorian Christ can never be the Lord of our devotion.” (pp.148-149, emphasis mine)There is only One in heaven worthy to be receive power, wealth, wisdom, strength, honor, glory, and praise: the Lamb Who Was Slain! (Revelation 5) If Jesus did not truly suffer as both God and human, he is not worthy to be worshiped as the Savior or Redeemer.

“If in Jesus the human is swallowed up in the divine, to such a point that he no longer functions as a human being, his sufferings are sham and are not like ours. He did not bear our sufferings, and therefore we cannot find vindication for those who now suffer. The Crucified One must be truly crucified. [...] He must be divine, for otherwise his suffering has no power to redeem, and he must also be human, for otherwise his suffering has nothing to do with ours. And the two must be joined in such a way that his true humanity is neither destroyed nor swallowed up in his divinity.” (p.149, emphasis mine)

Toward a Biblical Christology

González does not leave readers with all the many ways Christology has run aground the biblical witness and relied upon the appearance of human wisdom for truth about the nature of God. No, he closes out the chapter by constructing a way forward that relies upon God’s self-revelation in Christ for the truth about divine and human natures. It turns out, the Bible is handy in this regard:“...we do not know who God is, nor what it means to be fully human, apart from divine revelation. We must not approach divine revelation with a preconceived notion of God and accept in that revelation only that which agrees with such a notion. In the Older Testament we have the revelation of who God is—or, more precisely, of how God acts—as well as of what it means to be human. This revelation, Christians hold, comes to its culmination in the person od Jesus Christ, in whom the God of the Older Testament is most fully revealed, and in whom the true meaning of full humanity is also revealed. Therefore, we must not approach the person of Jesus Christ with an a priori notion of what it means to be divine—in this case drawn mostly from the Greek metaphysical tradition—or with an a priori notion of what it means to be human. The proper starting point for Christology is neither theology nor anthropology—nor a combination of the two—but Jesus himself as Scripture witness to him.” (p.151, emphasis mine)

“God’s very being is love, for-otherness. This is the Trinitarian God. This is the God revealed in Jesus Christ. What Jesus has done is precisely to open for us the way of love, to free us so that we too can begin to be for others. In being for others we are most truly human. And in being most truly human we are most Godlike. Indeed, God did become human so that we could become divine!” (p.155, emphasis mine)

1. Justo González, Mañana: Christian Theology from a Hispanic Perspective (Abingdon, 1990) [http://a.co/d/41ETGLR]