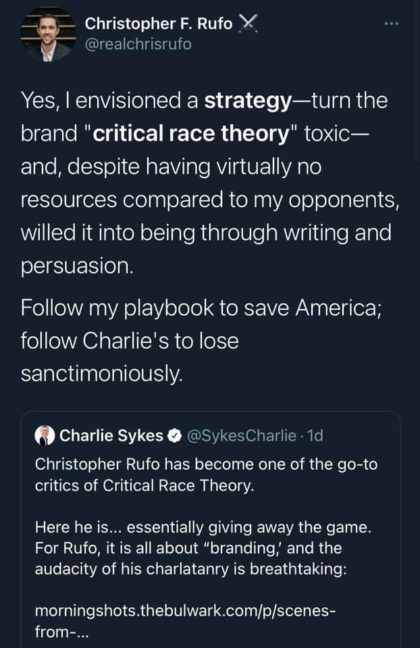

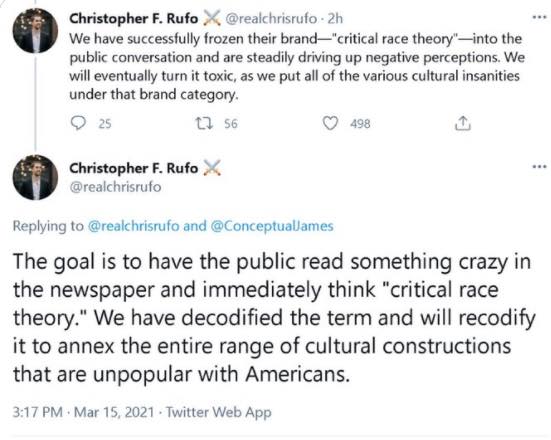

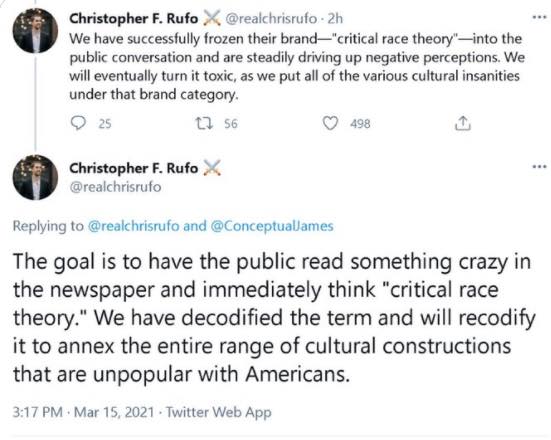

Today in the U.S. a highly effective strategy has been implemented to stifle any attempt to teach about systemic racism and its impact on society. A handful of conservative partisan operatives have turned the phrase “Critical Race Theory” (which is the name of an academic legal theory that’s been taught in law schools for decades) into a catch-all category for any subject related to racism that makes recalcitrant White Americans uncomfortable. The ramifications have been wide-spread and destructive. School board meetings have turned into battlefields, with White residents feeling emboldened to denounce concepts they don’t understand and to ‘cancel’ any teacher willing to teach them. Partisan politicians have also seized upon this strategy and wielded it like a bludgeon to pummel anyone speaking out against racial injustice. And the strategy to scapegoat “Critical Race Theory” is an intentionally deceptive strategy, as one of its architects candidly admits:

One of the subjects that’s been lumped into this pro-racism campaign because it makes White Americans nervous is privilege. The subject of privilege has a way of cutting to the heart of discussions about racial injustice by pinpointing the place where systemic racism hits home in our everyday lives. Privilege is often the presenting symptom of racial injustice. It’s the place where hidden norms, unspoken rules, and policy hidden in legalese comes to light. Unjust outcomes betray the injustice that was ‘baked into the cake.’ But privilege isn’t only a bugaboo for racists; privilege is also often a frustrating conundrum even for those who care deeply about redressing social injustices. It raises the important question: What can be done if a person has privilege but doesn’t want to unjustly benefit from it? Even for many anti-racists, the topic of privilege can feel overwhelming, which can lead to fatigue and even apathy.

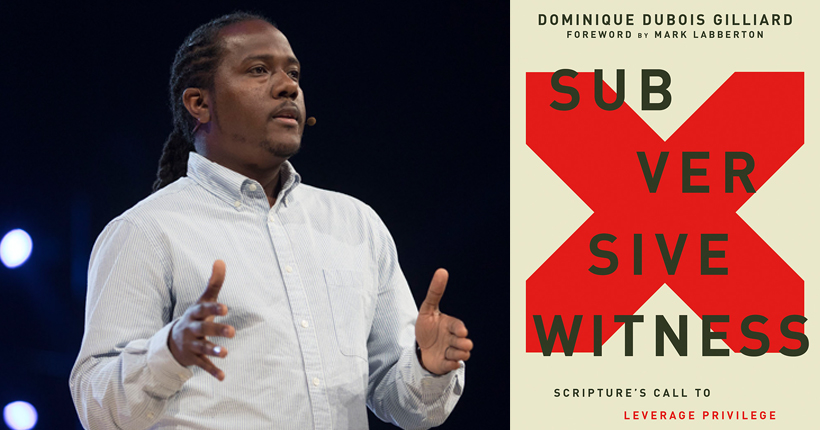

That’s why Dominique Gilliard’s new book Subversive Witness: Scripture’s Call to Leverage Privilege is such an important and timely resource. Gilliard confronts the reality of privilege head-on with laser focus. He doesn’t mince words in this book and he draws upon the wisdom of Scripture and the best scholarship available. He parses out what privilege is and isn’t, and also what can be done with it.

One of the subjects that’s been lumped into this pro-racism campaign because it makes White Americans nervous is privilege. The subject of privilege has a way of cutting to the heart of discussions about racial injustice by pinpointing the place where systemic racism hits home in our everyday lives. Privilege is often the presenting symptom of racial injustice. It’s the place where hidden norms, unspoken rules, and policy hidden in legalese comes to light. Unjust outcomes betray the injustice that was ‘baked into the cake.’ But privilege isn’t only a bugaboo for racists; privilege is also often a frustrating conundrum even for those who care deeply about redressing social injustices. It raises the important question: What can be done if a person has privilege but doesn’t want to unjustly benefit from it? Even for many anti-racists, the topic of privilege can feel overwhelming, which can lead to fatigue and even apathy.

That’s why Dominique Gilliard’s new book Subversive Witness: Scripture’s Call to Leverage Privilege is such an important and timely resource. Gilliard confronts the reality of privilege head-on with laser focus. He doesn’t mince words in this book and he draws upon the wisdom of Scripture and the best scholarship available. He parses out what privilege is and isn’t, and also what can be done with it.

One of the subjects that’s been lumped into this pro-racism campaign because it makes White Americans nervous is privilege. The subject of privilege has a way of cutting to the heart of discussions about racial injustice by pinpointing the place where systemic racism hits home in our everyday lives. Privilege is often the presenting symptom of racial injustice. It’s the place where hidden norms, unspoken rules, and policy hidden in legalese comes to light. Unjust outcomes betray the injustice that was ‘baked into the cake.’ But privilege isn’t only a bugaboo for racists; privilege is also often a frustrating conundrum even for those who care deeply about redressing social injustices. It raises the important question: What can be done if a person has privilege but doesn’t want to unjustly benefit from it? Even for many anti-racists, the topic of privilege can feel overwhelming, which can lead to fatigue and even apathy.

That’s why Dominique Gilliard’s new book Subversive Witness: Scripture’s Call to Leverage Privilege is such an important and timely resource. Gilliard confronts the reality of privilege head-on with laser focus. He doesn’t mince words in this book and he draws upon the wisdom of Scripture and the best scholarship available. He parses out what privilege is and isn’t, and also what can be done with it.

One of the subjects that’s been lumped into this pro-racism campaign because it makes White Americans nervous is privilege. The subject of privilege has a way of cutting to the heart of discussions about racial injustice by pinpointing the place where systemic racism hits home in our everyday lives. Privilege is often the presenting symptom of racial injustice. It’s the place where hidden norms, unspoken rules, and policy hidden in legalese comes to light. Unjust outcomes betray the injustice that was ‘baked into the cake.’ But privilege isn’t only a bugaboo for racists; privilege is also often a frustrating conundrum even for those who care deeply about redressing social injustices. It raises the important question: What can be done if a person has privilege but doesn’t want to unjustly benefit from it? Even for many anti-racists, the topic of privilege can feel overwhelming, which can lead to fatigue and even apathy.

That’s why Dominique Gilliard’s new book Subversive Witness: Scripture’s Call to Leverage Privilege is such an important and timely resource. Gilliard confronts the reality of privilege head-on with laser focus. He doesn’t mince words in this book and he draws upon the wisdom of Scripture and the best scholarship available. He parses out what privilege is and isn’t, and also what can be done with it.

Having privilege is not a sin, though sin has perverted our systems and structures in ways that engender sinful disparities. Privilege creates and expands anti-gospel inequities that infringe on collective liberation and shalom. It endows a few with educational, socioeconomic, political, vocational, and other advantages while disenfranchising many—simply because of how God intentionally created them. (p.13)One of the ways Gilliard unpacks the concept of privilege is through a theological reading of Scripture, by supplying biblical commentary on stories and characters with which/whom are already very familiar, but adding the lens of privilege. He retells the story of the Hebrew midwives, Esther, Moses, Paul & Silas, Jesus, and Zacchaeus. But in retelling these stories, we are now given lens through which we can recognize how privilege works and what to do with it. For example, Gilliard retells the very familiar story of Moses, but homes in on the cultural and ethnic dynamics at play when a Hebrew boy is raised in the Egyptian royal court. He narrates the ways Moses’s story illustrates solidarity and the leveraging of privilege for the sake of faithfulness to God and God’s people. Gilliard highlights a type of privilege we may not immediately recognize in the story: education privilege. Moses’s story of living in Midian for several decades and learning from his father-in-law, Jethro, can be viewed as an example of education privilege. It mirrors the experience of many Americans who have had the opportunity to leave (or escape) unhealthy environments and receive training and knowledge in a much safer and more supportive space. Gilliard challenges readers to consider how one might utilize such privilege. Will a person merely use their education to advance their own career, or will they use that know-how to reinvest back in the communities that need help? In fact, over and over, Gilliard demonstrates that throughout the Scriptures, God has been calling people to leverage the advantages they’ve been afforded for the sake of others, rather than exploiting those advantages for selfish gain. This is perhaps the core message of Subversive Witness. Being a disciples of Jesus means learning from Jesus and becoming more like him. And Jesus didn’t exploit his privilege, he leveraged it for the sake of others. This is precisely what the apostle Paul writes in the famous ‘Christ hymn’ of Philippians:

Who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross. (NRSV, emphasis mine) Few passages articulate Jesus’ ethic of sacrificial love as comprehensively as the Christ hymn (vv. 6-11). When we take on the mindset of Christ, we do nothing out of selfish ambition or conceit and refrain from exploiting our status and positions for selfish gain. We also, in humility, empty ourselves for the sake of the kingdom and our neighbors. This entails standing in solidarity with our neighbors when we have the option not to, placing the interests of others before our own, and prioritizing the peace and prosperity of our communities above our individual success—knowing that Scripture assures us that when our communities prosper, we do as well. In taking this Christlike posture, we move toward a collectivist pursuit of freedom, flourishing, and shalom. (p.104)I loved Gilliard’s critique of American ‘rugged individualism’ in this book. This has been an emphasis of my own pastoral teaching ministry for many years now, and it was heartening to read him highlighting it as well. I wish more pastors—particularly White Evangelicals (and even some who consider themselves ‘Progressive’)—understood this. In addition to racial injustice, the U.S. is also plagued by COVID-19. And if the last 18 months have revealed anything, it’s that there’s no bottom to the individualistic self-centeredness of many millions of Americans. Gilliard’s message of leveraging rather than exploiting privilege is precisely what millions of Americans who have prioritized their own comfort and partisan politics before the health and safety of their entire community by refusing to be vaccinated need to hear. Political freedom in this country is a privilege, and many who claim to be Christians are exploiting their freedom rather than leveraging it in the service of others. That's not the Jesus Way. I also think Gilliard demonstrates his own teaching on leveraging privilege in the book itself. He's had the privilege of learning from some of the most brilliant thinkers and experienced experts in the fields pertinent to this topic. But rather than merely repackaging their insights as his own, he draws readers’ attention toward this diverse array of scholars and practitioners. For example, he tells the story of Jonathan “Pastah J” Brooks, who’s work in the Englewood neighborhood of Chicago has helped to transform that community. And Gilliard points us to so many other important voices like Willie James Jennings, Justo González, Brenda Salter McNeil, and Bryan Stevenson. This is another way of leveraging privilege—by sharing not only the insight one has gained, but also the sources from which we draw it. In Subversive Witness, Dominique Gilliard weaves together wisdom from Scripture on privilege with insights from some of today’s leading thinkers and practitioners. Those who are humble enough to accept this wisdom will move further into living the Jesus Way and will be more equipped to partner with God in bringing shalom to our churches, communities, and world. I highly recommend this book.